Sponsored By

News

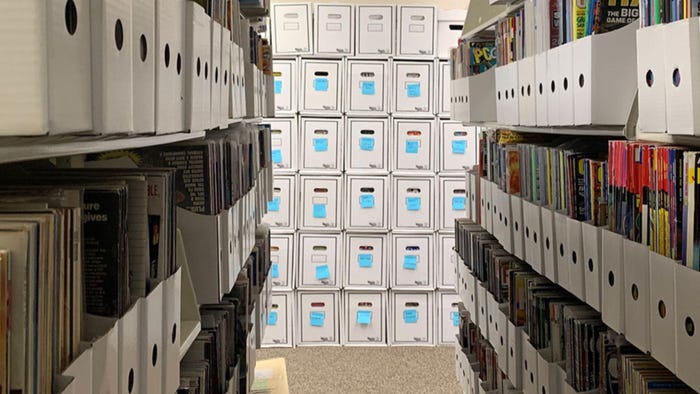

Screenshot of an archive within the Video Game History Foundation.

Business

ESA says members won’t support any plan for libraries to preserve games onlineESA says members won’t support any plan for libraries to preserve games online

The proposed plans for archiving older games at libraries don't strike a chord with the ESA.

Daily news, dev blogs, and stories from Game Developer straight to your inbox